sim_SIR <- function(TT, N = 1000, beta = .1, gamma = .01) {

S <- double(TT)

I <- double(TT)

R <- double(TT)

S[1] <- N - 1

I[1] <- 1

for (tt in 2:TT) {

contagions <- rbinom(1, size = S[tt - 1], prob = beta * I[tt - 1] / N)

removals <- rbinom(1, size = I[tt - 1], prob = gamma)

S[tt] <- S[tt - 1] - contagions

I[tt] <- I[tt - 1] + contagions - removals

R[tt] <- R[tt - 1] + removals

}

tibble(S = S, I = I, R = R, time = seq(TT))

}CANSSI Prairies — Epi Forecasting Workshop 2025

Compartmental Models, Renewal Equations, and \(R_t\) Estimation

Lecture 3

Daniel J. McDonald

Outline

- Compartmental Models

- Operationalizing Compartmental Models

- What is \(R_t\)?

- Estimating \(R_t\)

- Results and features of

{rtestim}

1 Compartmental models

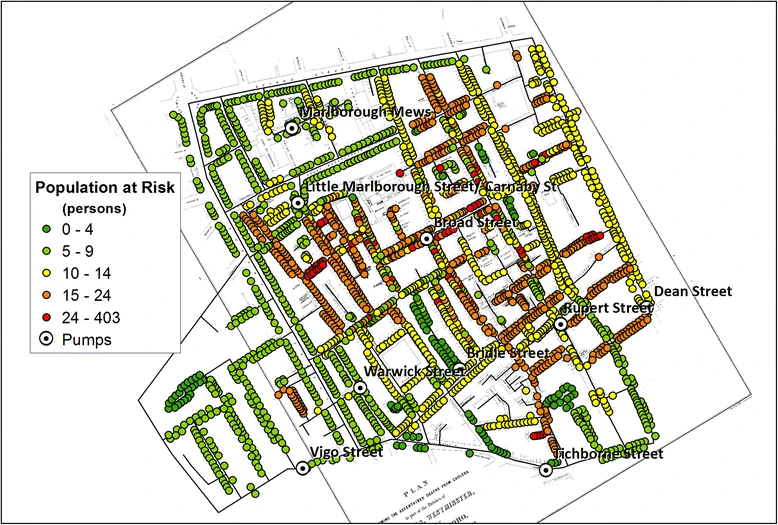

Mathematical modelling of disease / epidemics is very old

Daniel Bernoulli (1760) - studies inoculation against smallpox

John Snow (1855) - cholera epidemic in London tied to a water pump

Ronald Ross (1902) - Nobel Prize in Medicine for work on malaria

Kermack and McKendrick (1927-1933) - basic epidemic (mathematical) model

SIR-type (compartmental) models - Stochastic Version

Suppose each of N people in a bucket at time t:

Susceptible(t) : not sick, but could get sick

Infected(t) : sick, can make others sick

Removed(t) : recovered or dead; not sick, can’t get sick

- During period \(h\), each \(S\) meets \(kh\) people.

- Assume \(P( S \textrm{ meets } I \textrm{ and becomes } I ) = c\).

- Then \(P( S(t) \rightarrow I(t+h) ) = 1 - (1 - c I(t) / N )^{hk} \approx kchI(t) / N\).

- Therefore, \(I(t+h) | S(t),\ I(t) \sim \textrm{Binom}(S(t),\ kchI(t) / N)\).

- Assume \(P( I(t) \rightarrow R(t+h)) = \gamma h,\ \forall t\).

- Then \(R(t+h) | I_t \sim \textrm{Binom}(I(t),\ \gamma h)\).

SIR-type (compartmental) models - Stochastic Version

In the deterministic limit, \(h\rightarrow 0\)

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{dS}{dt} & = -\frac{\beta}{N} S(t)I(t)\\ \frac{dI}{dt} & = \frac{\beta}{N} I(t)S(t) - \gamma I(t)\\ \frac{dR}{dt} & = \gamma I(t) \end{aligned}\]THE SIR model is often ambiguous between these.

Typically, people mean the deterministic, continuous time version.

Data issues

Ideally we’d observe \(S(t)\), \(I(t)\), \(R(t)\) at all times \(t\)

Easier to observe new infections, \(I(t+h) - I(t)\)

Removals by death are easier to observe than removals by recovery,

so we mostly see \((R(t+h) - R(t)) \times \textrm{(death rate)}\)The interval between measurements, say \(\Delta\), is often \(\gg h\)

Measuring \(I(t)\) and \(R(t)\) (or their rates of change) is hard

- testing/reporting is sporadic and error prone

- Need to model test error (false positives, false negatives) and who gets tested

- Need to model lag between testing and reporting

Parameters (especially, \(\beta\)) change during the epidemic

- Changing behavior, changing policy, environmental factors, vaccines, variants, …

Connecting to Data

Likelihood calculations are straightforward if we can measure \(I_t\), \(R_t\) at all times \(0, h, 2h, \dots, T\)

Or \(I_0\), \(R_0\) and all the increments \(I_{t+h} - I_t\), \(R_{t+h} - R_t\)

Still have to optimize numerically

Likelihood calculations already become difficult if the time between observations \(\Delta \gg h\)

- Generally, \(\Delta \approx\) 1 day

- In principle, this just defines another Markov process, with a longer interval \(\Delta\) between steps, but to get the likelihood of a \(\Delta\) step we have to sum over all possible paths of \(h\) steps adding up to it

Other complications if we don’t observe all the compartments, and/or have a lot of noise in our observations

- We don’t and we do.

Connecting to Data

More tractable to avoid likelihood (Conditional least squares, simulation-based inference)

Intrinsic issue: Initially, everything looks exponential

- Hard to discriminate between distinct models

- If SIR is true, easier to estimate \(\beta - \gamma\) than \((\beta, \gamma)\) or \(\beta/\gamma\)

Can sometimes calibrate or fix the parameters based on other sources

- E.g., \(1/\gamma =\) average time someone is infectious in clinical studies

I have been thinking about how different people interpret data differently. And made this xkcd style graphic to illustrate this. pic.twitter.com/a8LvlmZxT7

— Jens von Bergmann (@vb_jens) March 17, 2021

These models can fit well in-sample

Track observed cases closely (they should)

Can provide nuanced policy advice on some topics

Many questions depend on modulating \(\beta\)

- What happens if we lock down?

- What happens if we mask?

- What happens if we have school online?

- Vaccine passport?

Vaccination modeling is easier, directly removes susceptibles

What about out-of-sample?

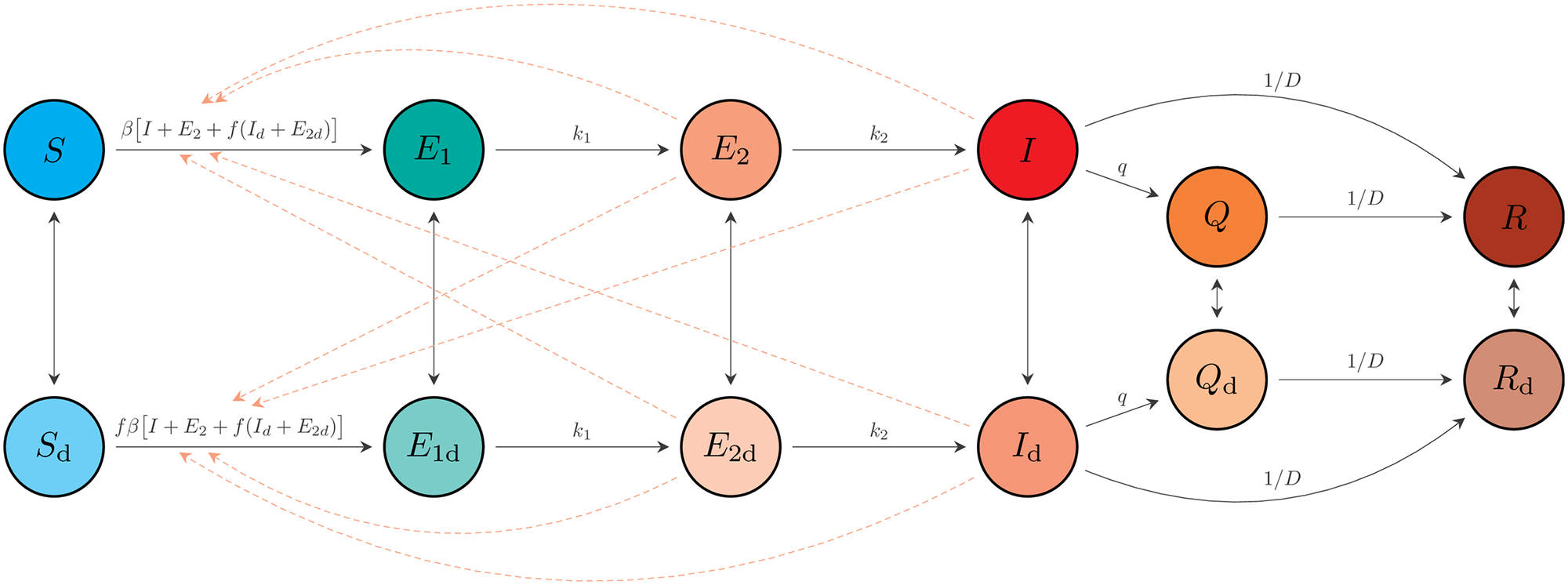

2 Operationalizing Compartmental Models

What does this “look like”?

What does this “look like”?

So far, just simulations, how do you fit one?

\[ \begin{aligned} x_{t+1} &= \textrm{OdeSolve}(x_t) + \epsilon_t\\ y_{t+1} &= \textrm{NegBinom}(\textrm{mean} = g(x_t),\ \kappa) \end{aligned} \]

- \(x_t\) is all the compartments

- \(y_t\) are some observations (cases and/or hospitalizations and/or deaths)

- Put priors on all the parameters (they are criminally underidentified)

Turn Bayesian Crank in Stan or similar until you’re done.

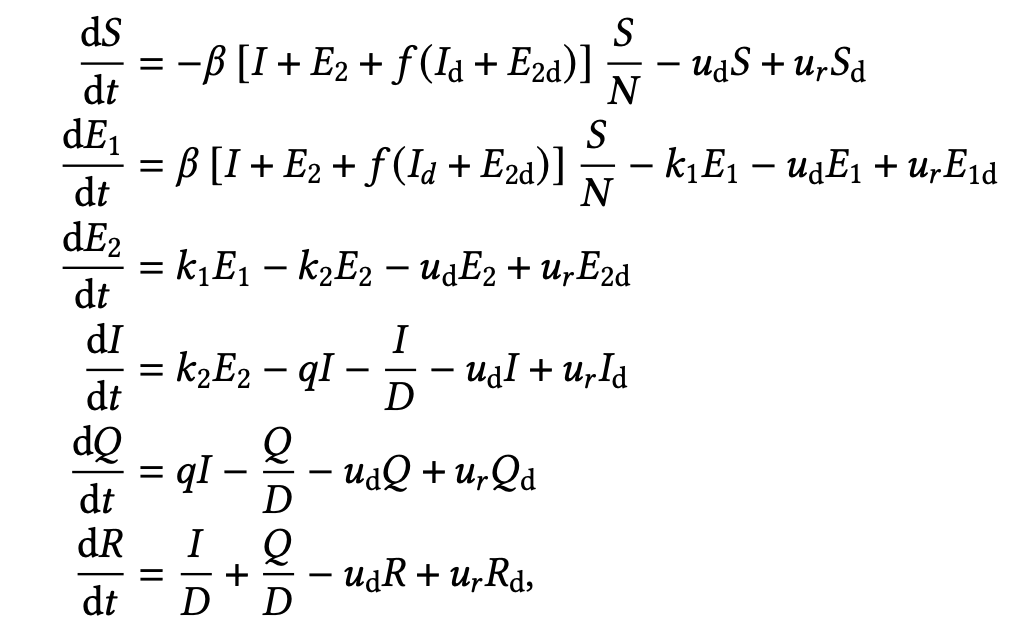

{covidseir} model

Rpackage: https://seananderson.github.io/covidseir/index.html- Paper link: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008274

Fit it to BC data and produce a forecast

samp_frac <- c(rep(0.14, 13), rep(0.21, 38), rep(0.37, nrow(early_bc) - 51))

f_seg <- with(early_bc, case_when(time_value == "2020-03-01" ~ 0, time_value >= "2020-06-01" ~ 3,

time_value >= "2020-05-01" ~ 2, time_value > "2020-03-01" ~ 1))

fit <- covidseir::fit_seir(daily_cases = early_bc$cases,

f_seg = f_seg, # change points in transmission

samp_frac_fixed = samp_frac, # fraction of infections that are tested

iter = 500, # number of posterior samples

fit_type = "optimizing") # for speed onlyUsing this or similar for forecasting

Needed to make lots of assumptions about future epi parameters

- Future transmission rate

- Future case ascertainment rate

- No new variants, or vaccinations, or influx of population

- People don’t lose immunity

- Etc., etc., etc.

More on these as forecasters a bit later.

Better described as scenario models.

3 What is \(R_t\)?

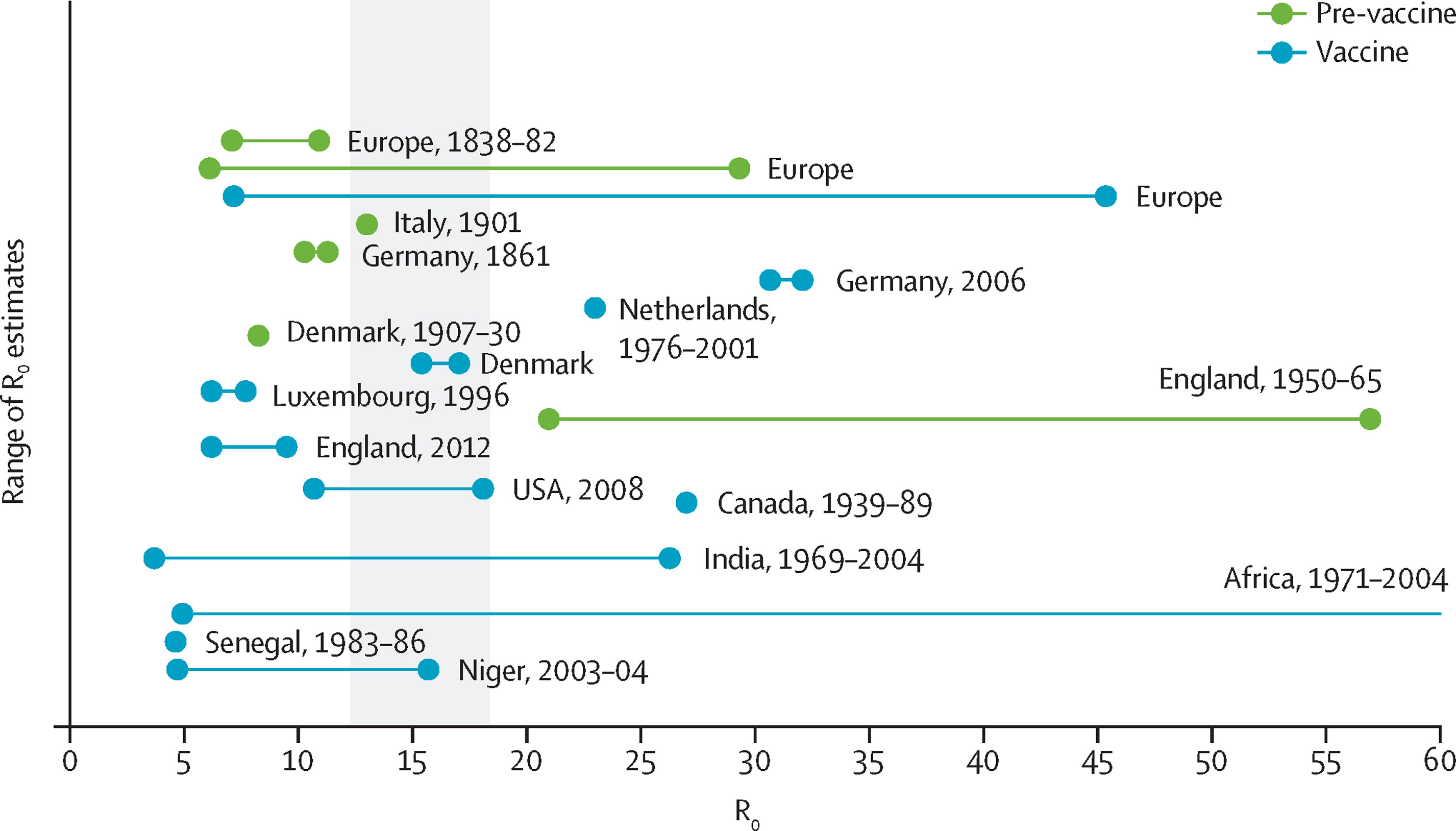

\(R_0\) basic reproduction number

Dates at least to Alfred Lotka (1920s) and others (Feller, Blackwell, etc.)

The expected number of secondary infections due to a primary infection

- \(R_0 < 1\) ⟹ the epidemic will die out

- \(R_0 > 1\) ⟹ the epidemic will grow until everyone is infected

\(R_0\) is entirely retrospective

It’s a property of the pathogen in a fully susceptible (infinite) population

Each outbreak is like a new sample

To estimate something like this from data, the “bonehead” way is to

- Wait until the epidemic is over (no more infections circulating)

- Contact trace the primary infection responsible for each secondary infection

- Take a sample average of the number caused by each primary

- Possibly repeat over many outbreaks

Of course no one actually does that

Lots of work on how to estimate \(R_0\)

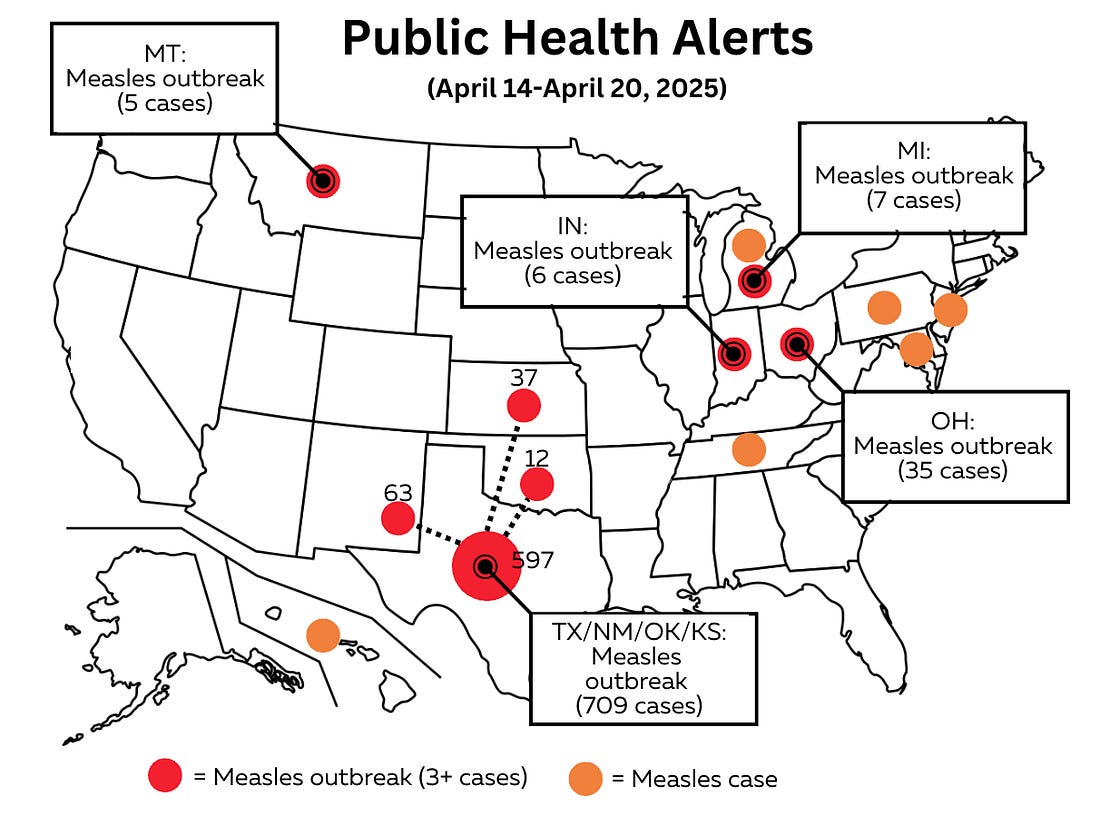

Effective reproduction number

Suppose \(s\)% of the population is susceptible

Then, “the” effective reproduction number \(R=sR_0\)

Allows you to reason about things like

The level of vaccine coverage necessary to prevent an outbreak from growing uncontrollably.

So, for measles, if \(R_0\approx 15\), the disease will die out if immunity is

\[ sR_0 \leq 1 \Longrightarrow 1-s \leq 1-1/R_0 \approx 93\% \]

\(R(t)\) — instantaneous reproduction number

The effective reproduction number in the middle of an outbreak

Some of the population is immune, others are infected, others susceptible

The expected number of secondary infections at time \(t\) caused by an earlier primary infection

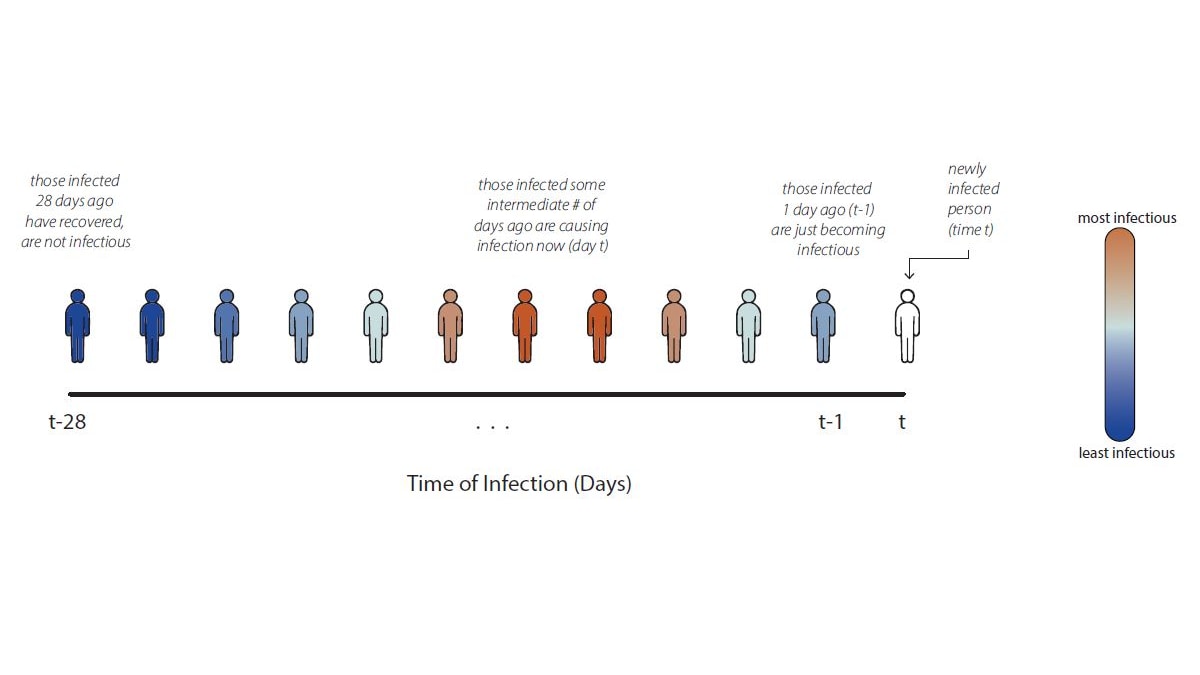

\(f(a) \geq 0,\ \forall a\) — the rate at which an infection of age \(a\) produces new infections

\[ \begin{aligned} R_0 &= \int_{0}^\infty f(a)\mathsf{d}a, \\ g(a) &= \frac{f(a)} {\int_{0}^\infty f(a)\mathsf{d}a} = f(a) / R_0. \end{aligned} \]

Can allow \(g(t, a)\), hold this fixed for now.

The generation interval distribution \(g(a)\)

\(R(t)\) and \(R_t\) — renewal equation

\(R(t)\) is defined implicitly through the renewal equation

\[ x(t) = R(t)\int_0^\infty x(t-a)g(a)\mathsf{d}a, \]

where \(x(t)\) are infections at time \(t\).

In discrete time,

\[ x_{t+1} = R_t\sum_{a=0}^\infty x_{t-a}\widetilde{g}_a = R_t (x * \widetilde{g}). \]

And stochasticly,

\[ \mathbb{E}\big[x_{t+1}\ |\ x_1,\ldots,x_{t}\big] = R_t\sum_{a=0}^\infty x_{t-a}\widetilde{g}_a = R_t (x * \widetilde{g}). \]

Most estimators start here: \[ \mathbb{E}\big[x_{t+1}\ |\ x_1,\ldots,x_{t}\big] = R_t\sum_{a=0}^\infty x_{t-a}\widetilde{g}_a. \]

- Assume \(\widetilde{g}\) is known

- Model \(x_t\ |\ x_1,\ldots,x_{t-1}\) as Poisson or Negative Binomial

- Turn some inferential crank

\(R_t\) for COVID-19 in the US

Source: US CDC Center for Forecasting Analytics

\(R_t\) in compartmental models

There is an equivalence between a compartmental model and the renewal equation.

\[ \begin{aligned} R_0 &= \beta / \gamma\\ x_{t+1} &= \beta S_{t} \sum_{k = 0}^t \big[(1-\gamma)^{k}\big] x_{t-k} = R_0 S_{t} \sum_{k = 0}^t \big[\gamma(1-\gamma)^{k}\big] x_{t-k} = R_{t}\sum_{k = 0}^t g(k)x_{t-k} \end{aligned} \]

4 Estimating \(R_t\)

Data issues

\(x_t\) is Infections, but we don’t ever see those

- Replace infections with cases

- Replace generation interval with serial interval

- Assume we have the serial interval

Serial interval distribution

Standard model for \(R_t\)

\[ \begin{aligned} \eta_t &= \sum_{a=0}^\infty y_{t-a}p_a,\\ \\ y_t\ |\ y_1,\ldots,y_{t-1} &\sim \textrm{Poisson}(R_t\eta_t). \end{aligned} \]

- Using \(y\) instead of \(x\) to be cases or hospitalizations or deaths, incidence

- Using \(p\) for serial interval distribution (discretized)

- The MLE for \(R_t\) is just \(y_t / \eta_t\).

- This has really high variance, but unbiased.

- So everybody smooths it.

The state of the art

{EpiEstim}(Cori, et al., 2013)

- Gamma prior on \(R_t\), but use a trailing window

- Super fast computationally

- Smoothness is ad hoc

{EpiFilter}(Parag, 2020)

- State space model

- One step smoothness: \(R_{s+1} \sim \textrm{Gaussian}(R_s,\ \alpha R_s)\)

- Uses a discretized particle filter-type algorithm

{EpiLPS}(Gressani, et al., 2022)

- Negative Binomial likelihood

- Smoothness via \(\log(R_t\eta_t) = \mathbf{B}_{t,:}\beta\)

- \(\mathbf{B}\) is cubic B-spline basis, weighted Ridge penalty on \(\beta\)

- More priors, use Metropolis Adjusted Langevin Algorithm

{EpiNow2}(CDC + CFA, Abbott, et al., 2023ish)

- Negative Binomial likelihood

- Smoothness via a GP prior

- Accommodates the sequence of delays from infection \(\longrightarrow\) ??

- Adjusts for real-time issues like partial reporting

- Big Bayesian MCMC in Stan. Very slow.

Our model

Let \(\theta_t := \log(R_t)\).

Use Poisson likelihood.

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{R} &= \exp(\widehat{\theta}) &\widehat{\theta} &= \mathop{\mathrm{argmin}}_\theta\; \eta^{\mathsf{T}}\exp(\theta) - \mathbf{y}^{\mathsf{T}}\theta + \lambda\Vert D^{(k+1)}\theta\Vert_1 \end{aligned} \]

- Convex, has a global optimum

- \(\lambda\) controls smoothness relative to data fidelity

- \(\ell_1\) penalty produces adaptive piecewise polynomials of order \(k+1\)

- Near minimax optimal for functions with bounded total variation

Local adaptivity — \(\ell_1\) vs. \(\ell_2\)

Polynomial order, \(k=0\)

\[

\begin{aligned}

D^{(1)} &= \begin{bmatrix}

1 & -1 & & & & \\

& 1 & -1 & & & \\

& & & \ddots && \\

& & & & 1 & -1

\end{bmatrix} \\ \\

&\in \mathbb{R}^{(n-1)\times n}

\end{aligned}

\]

Polynomial order, \(k=1\)

\[

\begin{aligned}

D^{(2)} &= \begin{bmatrix}

1 & -2 & 1 & & & \\

& 1 & -2 & 1 & & \\

& & & \ddots && \\

& & & 1 & -2 & 1

\end{bmatrix} \\ \\

&= D^{(1)}D^{(1)}\\ \\

&\in \mathbb{R}^{(n-k-1)\times n}

\end{aligned}

\]

Polynomial order, \(k=2\)

\[

\begin{aligned}

D^{(3)} &= \begin{bmatrix}

-1 & 3 & -3 & 1 & & \\

& -1 & 3 & -3 &1 & \\

& & & \ddots && \\

& & -1 & 3 & -3 & 1

\end{bmatrix} \\ \\

&= D^{(1)}D^{(2)}\\ \\

&\in \mathbb{R}^{(n-k-1)\times n}

\end{aligned}

\]

Estimation algorithm

\[ \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_\theta\; \eta^{\mathsf{T}}\exp(\theta) - \mathbf{y}^{\mathsf{T}}\theta + \lambda\Vert D^{(k+1)}\theta\Vert_1 \]

Estimation algorithm

\[ \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{\theta,\ {\color{BurntOrange} \alpha}}\; \eta^{\mathsf{T}}\exp(\theta) - \mathbf{y}^{\mathsf{T}}\theta + \lambda\Vert D^{(1)}{\color{BurntOrange} \alpha}\Vert_1\quad {\color{BurntOrange} \textrm{subject to}\quad \alpha = D^{(k)}\theta} \]

Estimation algorithm

\[ \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{\theta,\ \alpha}\; \eta^{\mathsf{T}}\exp(\theta) - \mathbf{y}^{\mathsf{T}}\theta + \lambda\Vert D^{(1)} \alpha\Vert_1\quad \textrm{subject to}\quad \alpha = D^{(k)}\theta \]

Alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM)

\[ \begin{aligned} \theta &\longleftarrow \mathop{\mathrm{argmin}}_\theta\ \eta^{\mathsf{T}}\exp(\theta) - \mathbf{y}^{\mathsf{T}}\theta + \frac{\rho}{2}\Vert D^{(k)}\theta - \alpha + u \Vert_2^2 \\ \alpha &\longleftarrow \mathop{\mathrm{argmin}}_\alpha\ \lambda\Vert D^{(1)} \alpha \Vert_1 + \frac{\rho}{2}\Vert D^{(k)}\theta - \alpha + u \Vert_2^2 \\ u &\longleftarrow u + D^{(k)}\theta - \alpha \end{aligned} \]

Estimation algorithm

\[ \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{\theta,\ \alpha}\; \eta^{\mathsf{T}}\exp(\theta) - \mathbf{y}^{\mathsf{T}}\theta + \lambda\Vert D^{(1)} \alpha\Vert_1\quad \textrm{subject to}\quad \alpha = D^{(k)}\theta \]

Alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM)

\[ \begin{aligned} \theta &\longleftarrow {\color{Cerulean}\textrm{Proximal Newton / Fisher Scoring}} \\ \alpha &\longleftarrow {\color{BurntOrange}\textrm{Fused Lasso Signal Approximator}} \\ u &\longleftarrow u + D^{(k)}\theta - \alpha \end{aligned} \]

Solve sequentially for \(\Vert (D^{\dagger})^{\mathsf{T}}(\eta - y)\Vert_\infty = \lambda_1 > \cdots > \lambda_M=\epsilon \lambda_1\).

5 Results and features of {rtestim}

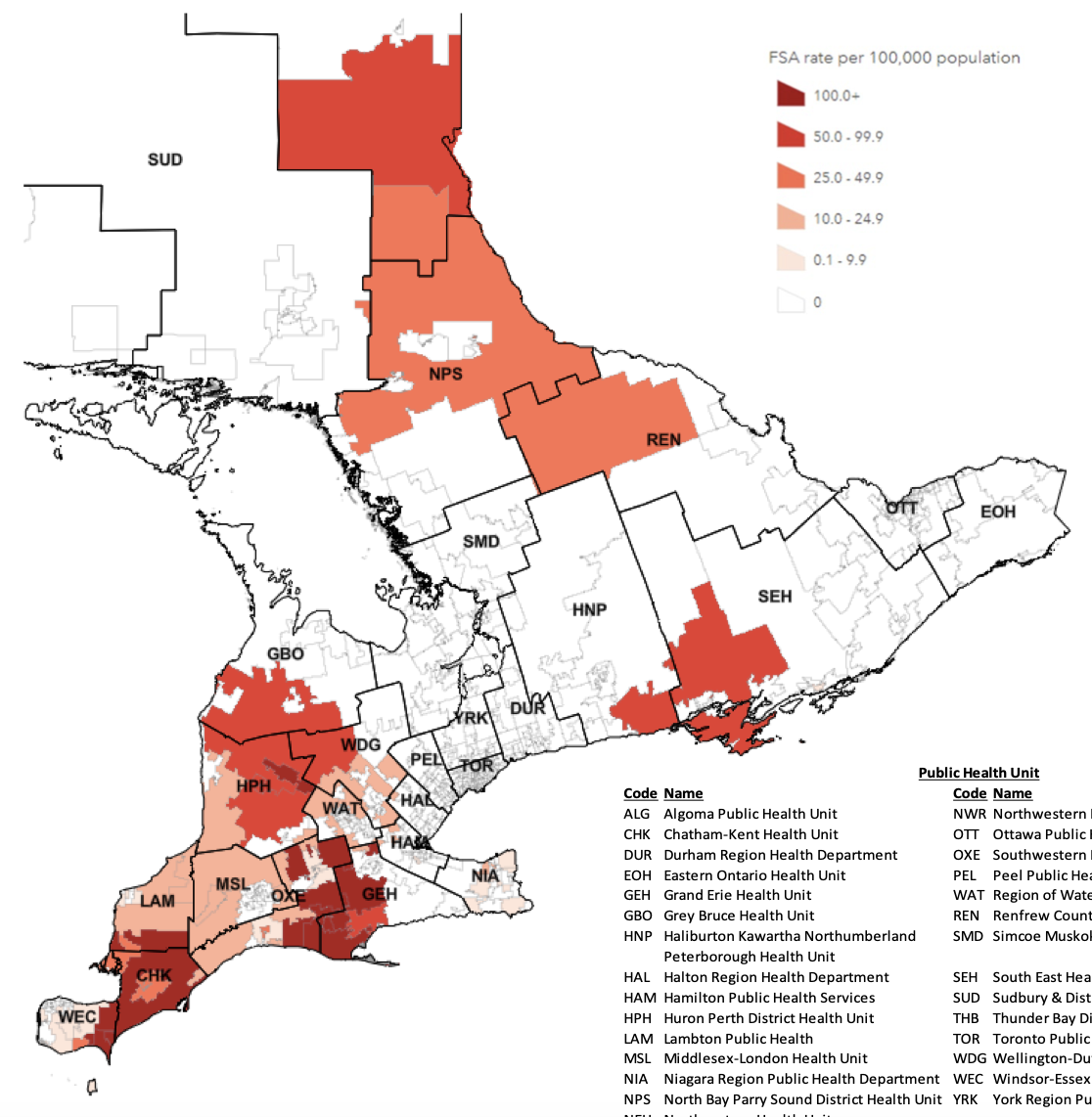

Canadian Covid-19 cases

\(R_t\) for Canadian Covid-19 cases

Reconvolved Canadian Covid-19 cases

Example simulations for different methods

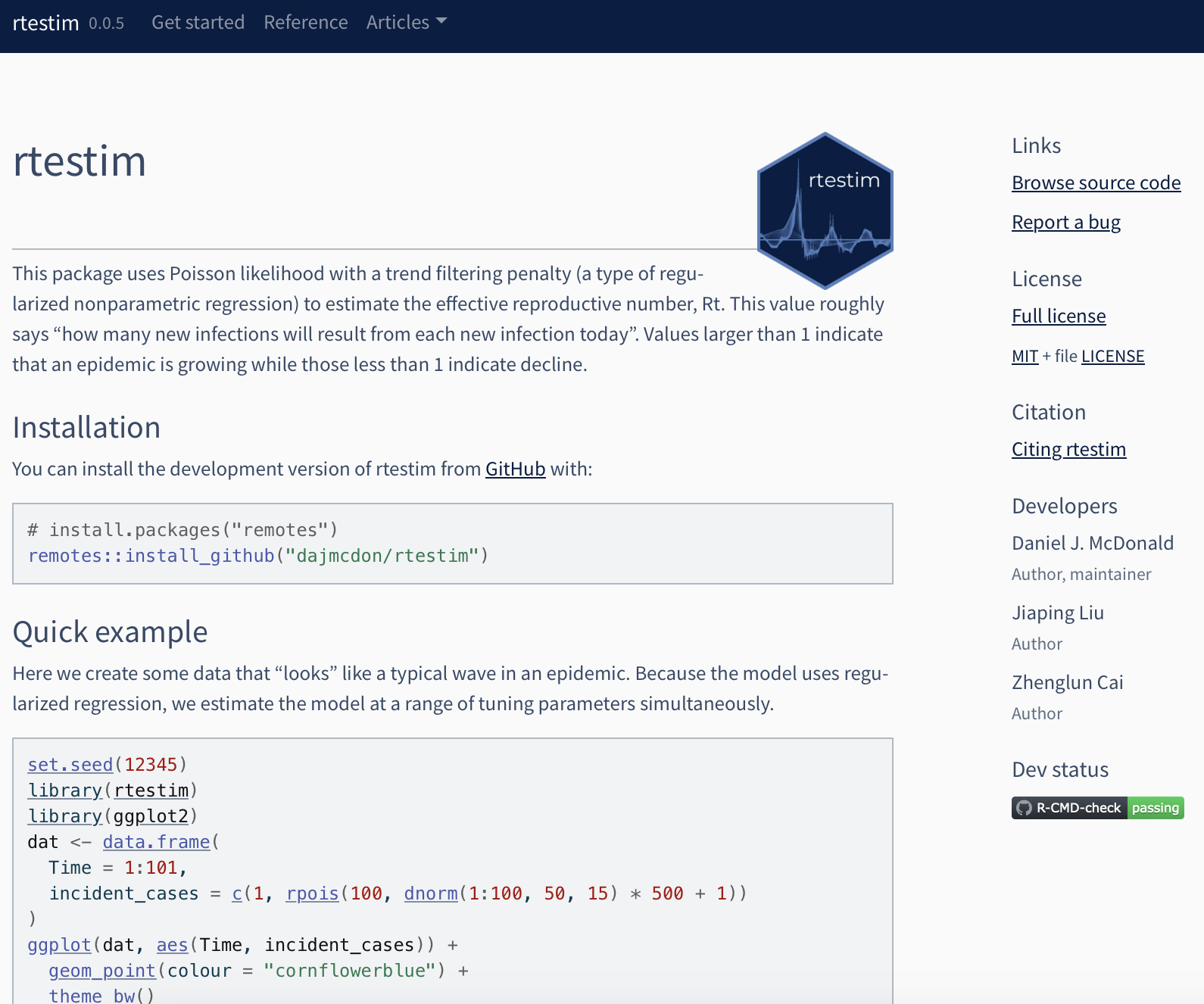

{rtestim} software

Guts are in C++ for speed

Lots of the usual S3 methods

Approximate “confidence” bands

\(\widehat{R}\) is a member of a function space

Arbitrary spacing of observations

Built-in cross validation

Time-varying delay distributions

{rtestim} software

Guts are in C++ for speed

Lots of the usual S3 methods

Approximate “confidence” bands

\(\widehat{R}\) is a member of a function space

Arbitrary spacing of observations

Built-in cross validation

Time-varying delay distributions

Approximation + Delta method gives

\[ \textrm{Var}(\widehat{R}) = \left(\textrm{diag}(\widehat{y}) + \lambda D^{\mathsf{T}}D\right)^{\dagger} \left(\frac{1}{\eta^2}\right) \]

{rtestim} software

Guts are in C++ for speed

Lots of the usual S3 methods

Approximate “confidence” bands

\(\widehat{R}\) is a member of a function space

Arbitrary spacing of observations

Built-in cross validation

Time-varying delay distributions

The solution is an element of the space of discrete splines of order \(k\) (Tibshirani, 2020)

- Lets us interpolate (and extrapolate) to off-observation points

- Lets us handle uneven spacing

{rtestim} software

Guts are in C++ for speed

Lots of the usual S3 methods

Approximate “confidence” bands

\(\widehat{R}\) is a member of a function space

Arbitrary spacing of observations

Built-in cross validation

Time-varying delay distributions

{rtestim} software

Wrapup and practice

- Basic compartmental modelling

- Difficulties in estimating compartmental models

- Standard epidemic parameters, \(R_0\)

- Discussion of \(R_t\) (model based vs nonparametric estimation)

- Some custom \(R_t\) software

Epi models — dajmcdon/canssip-epidata-2025